The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) will mount a large-scale survey of Sol LeWitt, foregrounding how the artist’s systems, instructions, and modular thinking redirected postwar art from object to idea. Framed around the notion of the “open structure,” the exhibition assembles wall drawings, three-dimensional structures, works on paper, and artist’s books, and is described by the museum as the first substantial survey of LeWitt’s art at a public museum in Japan. Curated by Ai Kusumoto of MOT and organized with the cooperation of the Estate of Sol LeWitt, the presentation situates the artist’s method—planning, rule-sets, and serial procedures—as the engine of the work. In the museum’s account, LeWitt’s contribution is not a style so much as a protocol: the artwork originates in an idea, plan, or process, and realization is a matter of execution according to that framework. The show’s lens makes plain how this approach redefined authorship and the afterlives of artworks in institutional settings.

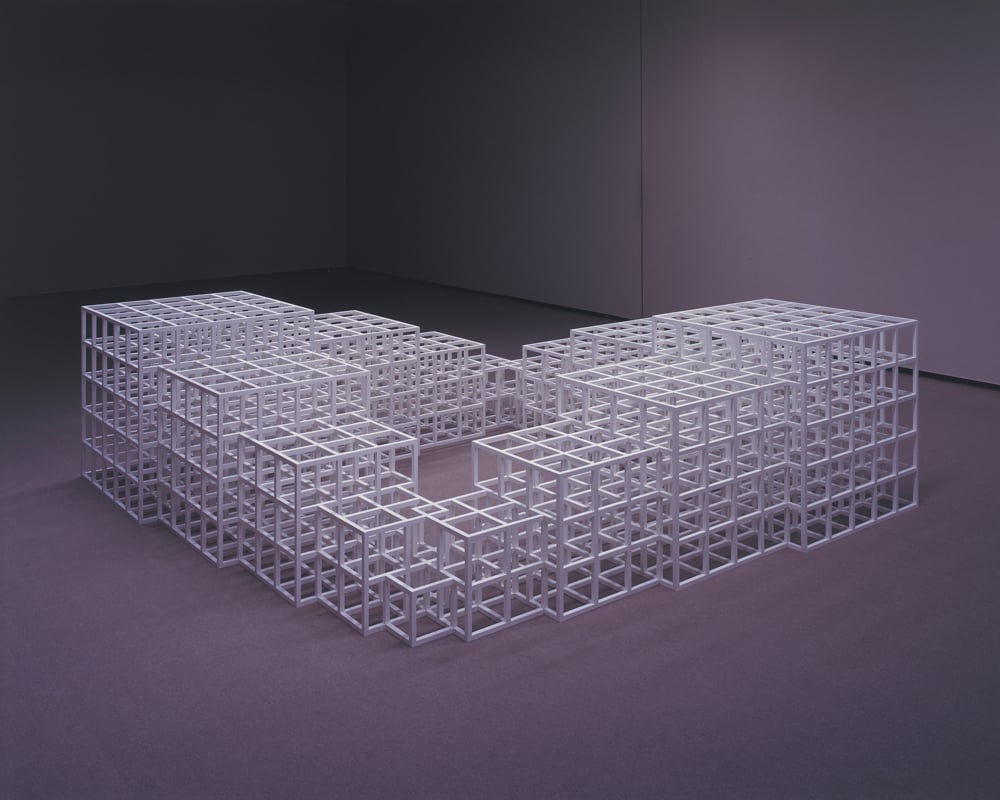

The exhibition emphasizes LeWitt’s formulation of conceptual practice, in which planning precedes and governs execution. The curatorial narrative clarifies that the emphasis on plan over product underpins the selection, including modular pieces that combine cube units to demonstrate how serial progression determines form, such as the structure titled One, Two, Three, Four, Five as a Square. Taken together, these works frame LeWitt’s studio as a site for designing procedures that can be carried out by others without compromising artistic intent. The museum positions this framework as a key to understanding the artist’s broader impact on how contemporary art is made, circulated, and reinstalled across contexts.

© 2025 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery.

A core of the survey focuses on wall drawings, one of LeWitt’s lifelong projects, which are executed by trained installers following the artist’s written instructions or diagrams. After display, these works are often painted over, an operational choice that underscores the primacy of the procedure and the portability of the idea. MOT presents six examples to show how a rule-set is translated into lines, arcs, and fields within the specific conditions of a gallery. In this format, authorship is deliberately distributed—between the originating concept and the hands that realize it—and permanence is recast as repeatability rather than physical endurance. The wall drawings make visible a system in action, turning the gallery into a space where instructions assume material form.

While many viewers associate LeWitt with austere black-and-white schemes and skeletal structures, the presentation also acknowledges phases that incorporate more complex forms and saturated color. The museum frames these developments as an extension of his method rather than a departure, maintaining simple systems and clear instructions while broadening the expressive range available to rule-based work. The result is a body of art that remains visibly anchored in procedural logic even as it explores different visual registers, from spare line progressions to vivid chromatic fields. Across these shifts, the underlying commitment to instructions, seriality, and modular reasoning remains constant.

The notion of “open structure” is most apparent in LeWitt’s cubic pieces, where faces are removed and framing edges remain visible. By exposing the scaffold of a form, these works make their own construction legible: what counts as a unit, how a sequence proceeds, and where a system permits variation. In the series commonly referred to as Incomplete Open Cube, the absence of particular edges evokes a structure caught mid-transformation—less a finished object than a proposition about how a form can be generated, reconfigured, and read. The museum reads this as a dismantling of perfection and invariability, consistent with LeWitt’s interest in rules that invite change rather than enforce stasis. The sculptures operate like diagrams in space, inviting viewers to reconstruct the rules that produced them.

Even when instructions are precise, every wall drawing registers the contingencies of place and the interpretation of those who execute it. Site, surface, scale, and hand inflect the outcome, and this variability is accepted as an integral component of the work rather than a flaw. The museum explicitly connects this stance to LeWitt’s view of ideas as shareable—art as a set of proposals that others can carry forward under defined conditions. This proposition goes beyond rhetoric; it is embedded in the procedural life of the works, which are reinstallable, adaptable to new environments, and renewed with each realization. Variability is not a compromise but a built-in feature of an art that privileges the circulation of ideas over the fixity of singular objects.

The survey also gives weight to LeWitt’s publishing activity and his role in creating pathways for idea-driven art outside traditional markets. To circulate concepts more freely, he produced numerous artist’s books and co-founded Printed Matter in New York with collaborators including critic Lucy R. Lippard, an organization dedicated to distributing artists’ publications independently of conventional channels. The presentation aligns this publishing work with the same philosophy that governs the wall drawings: a commitment to procedures that can be transmitted, understood, and enacted by many. Books and instructions function here as parallel vehicles—both treat reproducibility and dissemination as essential to the work’s meaning.

Within the broader history of contemporary practice, the museum situates LeWitt as a central figure in the shift toward treating artworks as spaces for thought rather than singular objects of contemplation. His writing and practice serve as reference points for instruction-based and concept-first art, where rules, algorithms, and modular systems become generative tools rather than constraints. By reconfiguring known structures—grids, cubes, sequences—he carved out a creative interval inside order itself, proposing that structure can open to possibility rather than close it down. The exhibition argues that this legacy remains current, informing ongoing debates about process, reproducibility, and institutional stewardship.

The curatorial approach asks viewers to read the gallery as an environment where ideas unfold through procedure, not as a warehouse of discrete objects. Lines, arcs, and modular units are presented as traces of conceptual activity rather than signatures of individual expression. The presentation encourages close attention to how simple rules can produce complexity and how distributed authorship—across artist, installers, and institutions—reshapes familiar notions of the unique art object. In this account, LeWitt’s contribution is a set of working principles for making and sharing art in public: clear instructions, open structures, and a willingness to let ideas travel.

For visitors, the exhibition takes place in Exhibition Gallery 1F of the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. Regular hours are 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., with tickets available until 30 minutes before closing, and the galleries are closed on Mondays and select additional closure days noted by the museum. Admission is listed as 1,600 yen for adults; 1,100 yen for university and college students and visitors over 65; 640 yen for high school and junior high school students; and free for elementary school children and younger. Inquiries can be directed to +81-3-5245-4111 (main), and further updates and access details are provided on the museum’s website. The exhibition is organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, operated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture, with the cooperation of the Estate of Sol LeWitt; Ai Kusumoto serves as curator.

Exhibition period: December 25, 2025 — April 2, 2026.