For millennia, aging has been viewed as an immutable, inevitable decline. However, a scientific revolution is underway, reframing aging not as a destiny to be endured but as a complex biological process that can be understood, measured, and potentially manipulated. This paradigm shift moves away from treating individual age-related diseases (AADs)—such as heart disease, neurodegeneration, and cancer—as separate afflictions. Instead, it targets the fundamental, shared mechanisms that drive them: the “hallmarks of aging”. At the heart of this revolution lie three interconnected pillars that are rapidly converging to redefine the future of medicine.

The first pillar is The Discovery: the groundbreaking work of Dr. Shinya Yamanaka, whose 2006 breakthrough in cellular reprogramming demonstrated that the fate of a cell is not a one-way street. The second is The Refinement: the evolution of this technology from creating stem cells to the more nuanced and therapeutically promising goal of “partial reprogramming.” This technique aims to reverse the biological clock of a cell, rejuvenating it without erasing its specialized identity. The third and most recent pillar is The Acceleration: the transformative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI), which is supercharging the pace of discovery, moving the field from slow, incremental progress to a new era of predictive and generative science.

This report provides an expert-level analysis of the scientific journey from the discovery of Yamanaka factors to the current AI-driven frontier of cellular rejuvenation. It examines the molecular mechanisms, pivotal experimental evidence, formidable clinical challenges, and the profound implications of this research for the future of human healthspan.

The Reprogramming Revolution: Shinya Yamanaka’s Nobel-Winning Discovery

Overturning Dogma: From a One-Way Street to a “Winding Road”

For decades, a central tenet of developmental biology was that cell differentiation is a terminal, unidirectional process. This concept is often visualized by Conrad Waddington’s “epigenetic landscape,” where a pluripotent cell at the top of a hill rolls down into one of several valleys, each representing a final, specialized cell type like a neuron or a skin cell. Once in a valley, the cell was thought to be locked into its fate. Foundational work by Sir John Gurdon in 1962 challenged this dogma by showing that the nucleus from a mature frog intestinal cell, when transplanted into an enucleated egg, could direct the development of a new tadpole, proving that the genetic information was not lost during differentiation.

Building on this, Dr. Shinya Yamanaka of Kyoto University embarked on what he would later call “The Winding Road to Pluripotency” in his Nobel Prize lecture. He hypothesized that a specific cocktail of transcription factors—proteins that control which genes are turned on or off—could rewind a mature cell’s developmental clock back to its embryonic-like, pluripotent state. This would achieve reprogramming without the need for eggs or embryos, a monumental scientific and ethical leap.

The “Magic Four”: Identifying the Yamanaka Factors

In a landmark 2006 paper, Yamanaka and his colleague Kazutoshi Takahashi described an elegant yet arduous experiment. They selected 24 candidate transcription factors known to be crucial for maintaining the “stemness” of embryonic stem cells (ESCs). Using retroviruses as delivery vehicles, they introduced these genes into mouse fibroblasts (a common type of skin cell). Through a meticulous process of elimination, removing one factor at a time from the pool of 24, they narrowed the list down to a core set of just four factors that were both necessary and sufficient to achieve this cellular time travel: Oct4 (Octamer-binding transcription factor-4), Sox2 (SRY-box transcription factor 2), Klf4 (Kruppel-like factor 4), and c-Myc.

The resulting cells, which they named induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), were functionally indistinguishable from ESCs. They could propagate indefinitely in culture and, when prompted, could differentiate into cells from all three primary germ layers—ectoderm (forming skin and nerves), mesoderm (forming muscle and bone), and endoderm (forming internal organs). This discovery, for which Yamanaka shared the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Gurdon, was revolutionary. It provided a potentially limitless source of patient-specific pluripotent cells for research and therapy, bypassing the ethical controversies that had long surrounded the use of human embryos.

The Molecular Mechanism of OSKM

The four Yamanaka factors (OSKM) do not work in isolation but as a tightly coordinated molecular team to orchestrate the complex process of reprogramming. Their roles are distinct yet synergistic:

- c-Myc: The Pioneer. c-Myc acts as the initial catalyst. In a mature cell, DNA is tightly wound around proteins in a structure called chromatin, making many genes inaccessible. c-Myc functions as a “pioneer factor,” binding to these condensed regions and opening up the chromatin structure. This action enhances cell proliferation and initiates widespread epigenetic changes, essentially preparing the ground for the other factors to work.

- Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (OSK): The Core Pluripotency Network. Once the chromatin is accessible, the core trio of OSK binds to the regulatory regions (enhancers and promoters) of thousands of genes. They work to silence the genes that define the cell’s mature identity (e.g., fibroblast-specific genes) while simultaneously activating a network of genes responsible for pluripotency, such as Nanog.

- The Self-Reinforcing Loop. A critical feature of this process is that the OSKM factors create a positive feedback loop. They activate their own genes and the genes of other pluripotency factors, establishing a stable, self-regulating network that maintains the cell in its new, pluripotent state.

Initial Hurdles and Limitations

Despite its brilliance, the initial iPSC technology was fraught with challenges that hindered its path to the clinic. The first was extremely low efficiency, with fewer than 1% of the treated cells successfully converting to iPSCs. More critically, there were profound safety concerns. The retroviruses used for delivery integrated their genetic payload randomly into the host cell’s genome, creating a risk of “insertional mutagenesis”—disrupting essential genes or activating cancer-causing ones.

The biggest single risk factor, however, was c-Myc itself. While it acted as a powerful accelerator for the reprogramming process, c-Myc is also a potent proto-oncogene, a gene that can drive cancer when dysregulated. Its inclusion dramatically increased the risk of the resulting iPSCs forming tumors (teratomas) upon transplantation. This created a fundamental trade-off at the heart of the technology: the very factor that made reprogramming efficient also made it dangerous. This tension between acceleration and risk was not merely a technical problem; it became the central scientific challenge that drove the next decade of research. The field’s immediate goal became to find ways to separate the beneficial, rejuvenating aspects of reprogramming from its dangerous, identity-erasing and tumorigenic properties. This quest led directly to the concept of partial reprogramming.

From Pluripotency to Rejuvenation: The Dawn of Partial Reprogramming

A Paradigm Shift: “Age Reprogramming” vs. Full Reprogramming

The initial goal of iPSC technology was to create new, healthy cells to replace old or diseased ones. However, a more radical idea began to emerge: what if instead of replacing cells, one could simply make old cells young again? This led to the concept of “partial reprogramming,” also known as “age reprogramming”. The core idea is to initiate the reprogramming process but stop it midway—long enough to reverse age-related cellular damage but before the cell loses its specialized function and becomes pluripotent.

This approach is predicated on the groundbreaking hypothesis that the molecular programs governing cellular age and cellular identity are separable. In theory, one could reset the “age” program—which includes epigenetic alterations, accumulated DNA damage, and mitochondrial decline—without completely rebooting the “identity” program that makes a neuron a neuron or a skin cell a skin cell. This is typically achieved by expressing the reprogramming factors only transiently or in cycles, often using the safer three-factor OSK cocktail (omitting the oncogene c-Myc) to prevent the cell from reaching the point of no return.

Preclinical Proof-of-Concept: Turning Back the Clock in Mice

A series of stunning preclinical studies provided powerful evidence that this was not just a theoretical possibility.

- The Ocampo Experiment (2016): The first major in vivo proof-of-concept came from the Salk Institute. Researchers used a progeroid mouse model (LAKI mice), which ages at an accelerated rate. By inducing cyclic, short-term expression of the four Yamanaka factors (OSKM), they observed a remarkable 33% increase in the mice’s median lifespan. The treated animals also showed systemic rejuvenation, with improved function in organs like the spleen and stomach and reduced spine curvature, all without developing cancer. This was the first definitive demonstration that reprogramming could extend lifespan and improve health in a living organism.

- The Rejuvenate Bio/Sinclair Lab Experiment (2023): An even more compelling study showed that these benefits were not limited to models of premature aging. Researchers administered a system-wide, inducible gene therapy delivering the three safer OSK factors to naturally aged, 124-week-old mice (roughly equivalent to a 77-year-old human). The results were staggering: the treatment extended the remaining median lifespan of these elderly mice by 109% and significantly improved their healthspan, as measured by a comprehensive frailty index.

- Targeted Rejuvenation (Lu et al., 2020): Research from David Sinclair’s lab at Harvard demonstrated that rejuvenation could be targeted to specific tissues to restore function. By delivering OSK via a safe adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector directly to the eyes of old mice, they were able to reset youthful gene expression and DNA methylation patterns in retinal ganglion cells. This not only promoted the regeneration of damaged axons but also restored vision in both aged mice and a mouse model of glaucoma.

These experiments collectively established that partial reprogramming is a potent rejuvenation strategy, capable of extending both lifespan and healthspan through systemic or targeted application.

Quantifying Rejuvenation: The Reversal of Aging Hallmarks

The effects of partial reprogramming are not just observable at the organismal level; they can be precisely quantified through molecular and cellular biomarkers. The therapy has been shown to reverse many of the canonical “hallmarks of aging”.

- Epigenetic Alterations: One of the most consistent findings is the restoration of a youthful epigenetic landscape. Partial reprogramming resets DNA methylation patterns, a key marker of biological age. In vitro studies on aged human cells have documented epigenetic age reductions of approximately 30 years after just 13 days of treatment.

- Cellular Senescence: The accumulation of senescent “zombie” cells is a major driver of aging. Partial reprogramming has been shown to clear these cells, evidenced by reduced staining for senescence-associated β-galactosidase and lower expression of key senescence markers like p16INK4a and p21WAF1/Cip1.

- Genomic Instability: The therapy bolsters the cell’s ability to maintain its genome. Levels of DNA damage, marked by γH2AX foci, are significantly reduced, while DNA repair pathways are upregulated.

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: The function of mitochondria, the cell’s powerhouses, is restored. This leads to reduced oxidative stress and more efficient energy production.

The success of these landmark studies, summarized in the table below, hinges on a critical principle: the “dose” of reprogramming matters. The cyclic protocols used by Ocampo et al. and the transient expression used in other studies were carefully designed to provide just enough of the reprogramming signal to trigger rejuvenation without pushing the cells over the edge into a pluripotent state, which carries the risk of cancer. Later in vitro work confirmed this, showing that there is an optimal duration of factor expression—for example, 13 days in one study—that maximizes epigenetic reversal, while longer durations become less effective or even detrimental. This reveals that rejuvenation is not a simple on/off switch but a tunable, dose-dependent process. The central engineering challenge for turning this science into medicine is therefore to find and precisely control this therapeutic window: delivering a sufficient dose for rejuvenation while ensuring an absolute barrier against loss of cell identity and tumorigenesis. This need for precision and optimization is precisely where AI has begun to play a transformative role.

Table 1: Landmark Partial Reprogramming Studies

| Model | Reprogramming Protocol | Key Outcome(s) |

| LAKI Progeroid Mice | Cyclic OSKM expression (2 days on, 5 days off) | 33% increase in median lifespan; amelioration of age-associated phenotypes. |

| Aged Wild-Type Mice (124 weeks old) | Systemic AAV-OSK delivery (1 week on, 1 week off) | 109% increase in remaining median lifespan; improved frailty scores. |

| Aged/Glaucoma Mice | Intra-orbital AAV-OSK delivery | Restoration of youthful gene expression and DNA methylation; axon regeneration and vision restoration. |

| Aged Human Fibroblasts (in vitro) | Lentiviral OSKM delivery (13 days) | ~30-year reduction in epigenetic age as measured by DNA methylation clocks. |

The AI Accelerator: Supercharging the Search for the Fountain of Youth

Taming Complexity: Why Biology Needs AI

The progress from Yamanaka’s discovery to successful in vivo rejuvenation was the result of years of painstaking, trial-and-error experimentation. The underlying biological systems are staggeringly complex. Optimizing a single protein like SOX2, which is composed of 317 amino acids, involves navigating a theoretical design space with more possibilities than atoms in the universe (on the order of 101000). Exploring this space with traditional laboratory methods is impossible. This is where Artificial Intelligence, particularly deep learning and large language models (LLMs), has emerged as an indispensable tool. AI can analyze vast datasets to identify subtle patterns, predict the functional consequences of genetic changes, and, most importantly, generate novel biological designs that exceed the capabilities of human intuition.

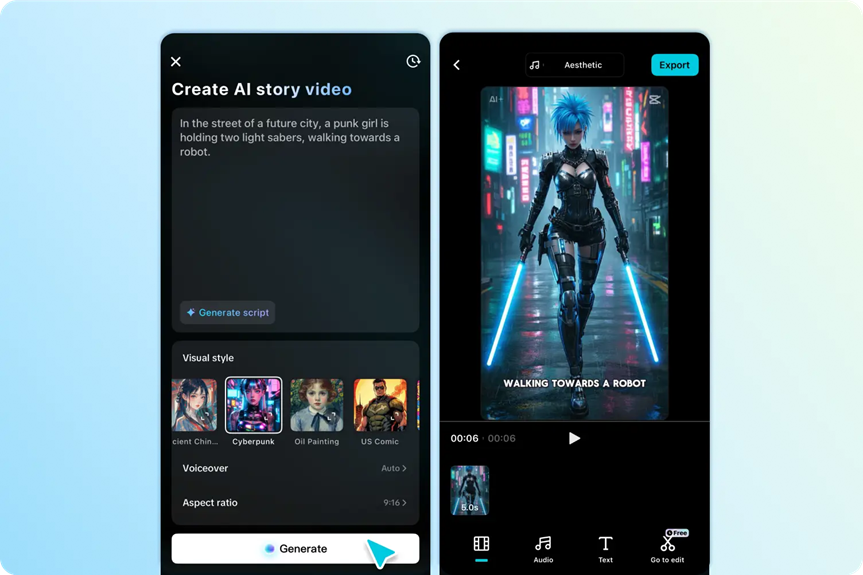

Case Study: OpenAI and Retro Biosciences’ Breakthrough

A dramatic demonstration of this new paradigm was unveiled in August 2025 through a collaboration between OpenAI and the longevity startup Retro Biosciences. Their goal was to use generative AI to engineer superior versions of the Yamanaka factors.

- GPT-4b micro: They developed a specialized AI model, a scaled-down version of GPT-4o, that was further trained on a massive, curated dataset of protein sequences, biological literature, and tokenized 3D structural data. This custom model was designed to understand the complex “language” of proteins—the rules governing how amino acid sequence dictates structure and function—and to generate novel sequences with specific, desired properties, including for proteins with disordered regions, like the Yamanaka factors.

- Engineering Better Factors: Retro’s scientists prompted GPT-4b micro to design new variants of SOX2 and KLF4. The AI produced hundreds of novel sequences, dubbed “RetroSOX” and “RetroKLF,” many of which differed from the natural versions by more than 100 amino acids.

- Staggering Results: When tested in the lab, the AI-designed factors were not just functional; they were dramatically superior.

- Efficiency Boost: The best combination of AI-engineered factors resulted in a greater than 50-fold higher expression of key stem cell reprogramming markers compared to the original Yamanaka factors.

- Accelerated Timeline: The reprogramming process was slashed from a typical three-week duration to as little as seven days.

- Enhanced Safety Profile: Critically, the AI-designed factors also demonstrated enhanced DNA damage repair capabilities. Cells treated with the new cocktail showed a significant reduction in DNA double-strand breaks (measured by γ-H2AX foci) compared to cells treated with the original factors, suggesting a more robust and potentially safer rejuvenation process.

- High Hit Rate: The AI’s success rate was remarkable. Over 30% of its SOX2 suggestions and nearly 50% of its KLF4 suggestions outperformed the wild-type versions—a massive leap over the less than 10% hit rate typical of traditional, high-throughput screening methods.

This collaboration marked a fundamental turning point. AI was no longer just an analytical tool for interpreting existing data; it had become a generative partner in the lab, capable of creating novel, high-performance biological machinery. This demonstrated a shift from an era of biological discovery to an era of biological design, with AI acting as an in-silico engine of evolution, compressing years of R&D into a matter of weeks.

Measuring Success: AI-Powered Epigenetic Clocks

To effectively design and test rejuvenation therapies, researchers need an accurate yardstick to measure biological age. Chronological age is a poor proxy for health, as individuals age at different rates. The solution came in the form of “epigenetic clocks,” pioneered by scientists like Steve Horvath. These are machine learning algorithms trained to predict biological age by analyzing patterns of DNA methylation (DNAm)—chemical tags on DNA that change predictably with age—at hundreds of specific sites across the genome.

Initially built with simpler linear regression models, these clocks are now being supercharged by deep learning. Advanced neural network-based clocks, such as DeepMAge and AltumAge, can capture the complex, non-linear interactions within the epigenome, yielding far more accurate and robust predictions of biological age. These AI-powered clocks are now the gold standard for quantifying the success of partial reprogramming, providing the precise, objective data needed to validate that a therapy has truly turned back the clock at a molecular level.

The Road to the Clinic: Hurdles, Players, and the Future of Medicine

The Safety Imperative: Mitigating the Teratoma Risk

The single greatest safety obstacle to translating any therapy derived from pluripotent or reprogrammed cells into human use is the risk of teratoma formation. A teratoma is a tumor that can arise from even a single residual, undifferentiated cell left in a therapeutic preparation, and it contains a chaotic mix of tissues like hair, teeth, and bone. Preventing teratomas is non-negotiable, and the teratoma assay in immunodeficient mice remains the “gold standard” safety test required by regulatory agencies.

The very design of partial reprogramming—halting the process before cells become fully pluripotent—is the primary strategy to mitigate this risk. However, multiple layers of safety engineering are being developed to create a fail-safe system:

- Safer Delivery Methods: The field has moved decisively away from integrating retroviruses. Modern approaches use non-integrating vectors like adenoviruses, Sendai viruses, or transient delivery systems like mRNA, which deliver the reprogramming factors without permanently altering the cell’s DNA.

- Engineered “Suicide Genes”: A powerful strategy involves building a “kill switch” into the therapeutic cells. One example is the inducible Caspase-9 (iCaspase-9) system. Cells are engineered to express this gene, which can be activated by a specific, otherwise inert drug. If any unwanted cell growth is detected, administering the drug triggers apoptosis (programmed cell death), selectively eliminating the dangerous cells.

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: An alternative approach uses drugs that specifically target and kill pluripotent cells. For instance, the survivin inhibitor YM155 has been shown to be highly effective at eradicating residual iPSCs from a population of differentiated cells without harming the desired therapeutic cells.

The Titans of Longevity: Key Industry and Academic Players

The immense promise of cellular rejuvenation has attracted unprecedented levels of funding and talent, creating a vibrant ecosystem of academic labs and biotech companies.

- Altos Labs: Launched in 2022 with a staggering $3 billion in initial funding, Altos Labs is arguably the most ambitious player in the space. Its stated mission is to “unravel the deep biology of cell rejuvenation” to reverse disease. The company has assembled a dream team of scientific leaders, including Nobel laureates Shinya Yamanaka (as a senior scientific advisor) and Jennifer Doudna, and is led by industry veterans like CEO Hal Barron.

- Calico Life Sciences: Founded in 2013, Calico is Google/Alphabet’s well-funded and famously secretive foray into the biology of aging. Led by former Genentech CEO Arthur Levinson, its mission is to understand the fundamental mechanisms of aging to develop interventions that enable longer, healthier lives. Calico has a long-standing, billion-dollar research and development collaboration with the pharmaceutical giant AbbVie.

- David Sinclair’s Lab (Harvard) and Spinoffs: The academic lab of Dr. David Sinclair has been a powerhouse of influential research. His “Information Theory of Aging,” which posits that aging is a reversible loss of epigenetic information, has provided a strong theoretical framework for the field. His lab’s key discoveries in vision restoration and lifespan extension have led to the formation of companies like Life Biosciences, which is developing specific drug candidates for age-related diseases of the eye and liver.

A clear bifurcation is emerging in the commercial landscape. On one hand, large, heavily funded “moonshot” entities like Altos and Calico are focused on deep, fundamental biology with very long research horizons, backed by tech billionaires and corporations willing to wait a decade or more for breakthroughs. On the other hand, more nimble, application-focused biotechs like Life Biosciences and Rejuvenate Bio are pursuing more traditional therapeutic development paths, targeting specific diseases with clearer and faster routes to clinical trials. This dynamic ecosystem, where foundational discoveries from the larger players can fuel the product pipelines of the smaller ones, is likely to accelerate the entire field’s progress.

Therapeutic Horizons: Targeting Age-Related Diseases

The ultimate goal of this research is not immortality, but the treatment and reversal of specific, debilitating diseases of aging. The first human applications are likely to target areas where the need is high and the delivery is feasible.

- Ophthalmology: Diseases causing vision loss, such as glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration, are prime initial targets. The eye is relatively accessible for local drug delivery and is “immune-privileged,” reducing the risk of immune rejection. The strong preclinical success in restoring vision in mice and non-human primates makes this a leading area of development.

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: The potential to rejuvenate or replace dying neurons offers hope for devastating conditions like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and ALS. Research is exploring how reprogramming can restore neuronal function and protect against the inflammatory processes that drive these diseases.

- Musculoskeletal Conditions: Osteoarthritis, which affects millions and is characterized by the degradation of joint cartilage, is another major target. While current stem cell therapies have shown mixed results, the prospect of using partial reprogramming to rejuvenate a patient’s own cartilage-producing cells or reduce joint inflammation is an active area of research.

- Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases: Preclinical studies are exploring the use of rejuvenation to repair heart tissue after a heart attack, improve the function of aged blood vessels, and restore youthful metabolic function in organs like the liver.

Redefining Healthspan in the 21st Century

The journey from Shinya Yamanaka’s foundational discovery to the AI-accelerated frontier of cellular rejuvenation represents one of the most exciting and potentially transformative narratives in modern science. We have moved from a world where cellular fate was considered immutable to one where it is programmable. We have evolved from the goal of creating new cells to the more profound ambition of making old cells young again. And now, with the advent of generative AI, we are transitioning from discovering the tools of rejuvenation to actively designing better, safer, and more efficient ones.

The most significant implication of this work is the fundamental shift in focus from lifespan to healthspan. The goal is not merely to add years to life, but to add healthy, vibrant, and functional life to years. Cellular rejuvenation technology is the most powerful tool yet conceived to close the ever-widening gap between how long we live and how long we live well.

However, as we stand on the precipice of this new era, we must also confront the profound ethical and societal challenges it presents. The question of equitable access is paramount: will these likely expensive therapies become a luxury for the wealthy, exacerbating global health disparities?. We must also grapple with the regulatory and philosophical question of whether aging itself should be classified as a disease to be “cured”. Finally, the long-term safety of resetting our cellular epigenomes remains an open question that can only be answered through rigorous, long-term clinical study.

These challenges are formidable, but the potential reward is immense. Cellular rejuvenation is not a quest for immortality. It is the pursuit of the ultimate form of preventative medicine—a new therapeutic paradigm focused on proactive regeneration and the restoration of health at its most fundamental level. If successful, it promises a future where humanity can live not just longer, but healthier, more resilient, and more vibrant lives.

Cracking the Code of Aging

How the convergence of Nobel Prize-winning biology and Artificial Intelligence is unlocking cellular rejuvenation.

Longevity Research Funding

$8.2 Billion

Invested in longevity and anti-aging startups in the last decade.

A Pivotal Discovery

2006

Year Shinya Yamanaka discovered cellular reprogramming.

The Four Keys to Cellular Youth

In 2006, Shinya Yamanaka identified four transcription factors that can rewind a cell’s biological clock. These “Yamanaka Factors” are the foundation of modern rejuvenation science.

🧬

Oct4

A crucial factor for maintaining pluripotency, the cell’s ability to become any other cell type.

🔬

Sox2

Works with Oct4 to activate genes that maintain the stem-cell state and cell identity.

🔑

Klf4

A “pioneer factor” that helps open up tightly packed DNA, allowing reprogramming to begin.

⚡

c-Myc

Accelerates the reprogramming process but is also linked to cancer, making it a target for replacement.

Two Paths of Reprogramming

The goal of rejuvenation is not to create blank-slate stem cells, but to make existing cells younger. This requires a delicate balance known as partial reprogramming.

Aged Somatic Cell

(e.g., Skin, Heart, Neuron)

Path 1: Full Reprogramming

Continuous exposure to Yamanaka factors.

Result: iPSC

Cell identity is lost. High therapeutic potential for tissue generation, but high risk of tumors in vivo.

Path 2: Partial Reprogramming

Brief, cyclical exposure to AI-optimized factors.

Result: Rejuvenated Cell

Cell identity is retained. Epigenetic markers of aging are removed, restoring youthful function with lower risk.

AI: The Research Superpower

Artificial Intelligence is revolutionizing the speed and precision of rejuvenation research, finding optimal solutions in a vast biological landscape that would be impossible to navigate manually.

AI accelerates discovery by testing millions of factor combinations virtually, identifying promising candidates for physical lab experiments.

Future Therapeutic Targets

Cellular rejuvenation isn’t about immortality; it’s about extending healthspan by targeting the root causes of age-related diseases across multiple physiological systems.

The initial focus is on localized treatments (like eye diseases) before moving to systemic therapies for whole-body rejuvenation.